A fabricated coffee meeting. Key facts withheld or walked back. A “great party story” about a sexual assault—which the accuser now says may not have actually happened.

What happens when an activist’s legacy is tarnished by the story of an old friend who later says it could have all been a misunderstanding? And how do we process such an anomaly in an era of overdue social justice?

***

Thirty-six years before he joined the chorus of outrage over sexual misconduct, Scott Brunton knew about getting hit on by older men.

An aspiring model, tall and blonde, Brunton’s first shot at working with a famous photographer immediately turned foul.

“I’d like to do your entire portfolio,” the photographer told Brunton when he arrived at the older man’s home. “And,” he added, “I’d like to sleep with you.”

Brunton was floored. When he declined, the photographer said, “Well, I guess this won’t work then.” The young model left without any photos.

Events like this in his early 20s changed Brunton’s view of romance and relationships. The former model, who said he was voted “Most Naive” in his Oregon high school class, “became very wary of people—men—who may have wanted just to get into my pants.”

Of all these unwanted advances, the most noteworthy—the one that would, decades later, put him in the public spotlight—involved a famous actor: Star Trek star George Takei.

Or so Brunton said last November, when he claimed that in 1981, he and Takei, then 44, had gone out together and ended up in the actor’s condo late at night. There, he drank cocktails Takei had made, became woozy and found himself on a bean bag chair. Then, according to Brunton, the actor pulled down Brunton’s pants while the model was barely conscious. Coming to and startled, 24-year-old Brunton bolted.

Nearly four decades later, Brunton, who said he’d told the story to friends “maybe 20 times,” typed the words, “George Takei sexually assaulted me,” in an email to The Hollywood Reporter, accusing the actor of groping him.

The reckoning was immediate. Within hours, the THR story went absolutely viral. Twitter similarly exploded with users accusing Takei of drugging Brunton and labeling Takei as a rapist. Eighty-year-old Takei denied Brunton’s accusation, saying he couldn’t even remember the guy.

But disgusted fans abandoned Takei, who had paired his Lieutenant Sulu fame with hourly tweets on human rights and politics to become an iconic critic, a foil to Donald Trump and promoter of LGBTQ rights with over 10 million followers. His publishing partners dumped him. Saturday Night Live dropped his name in a skit about sex offenses. Donald Trump Jr. gleefully tweet-accused Takei of hypocrisy.

Wrong again Georgie… I guess you have a bit more free time to read #fakenews now that it’s a bit tougher to ply kids with alcohol to assault them??? You know with all the added scrutiny. https://t.co/xUbvbfhMxN

— Donald Trump Jr. (@DonaldJTrumpJr) December 10, 2017

Was this an uncharacteristic lapse? Or was it the first hint of a hidden pattern, a dark side Takei kept from public view for decades?

I had my own reasons for wanting the answer.

Though I never spoke with him, Takei was one of several people I profiled while writing a pop-science book about human collaboration. In one chapter, I examined Takei’s fight against homophobia and Asian American discrimination, including through his hit Broadway musical Allegiance, based on the story of his own childhood incarceration in WWII internment camps.

The THR article broke as my publisher, Penguin, was reading the final draft of my manuscript. The question: What now?

If Takei was indeed a creep, I was inclined to remove him from my book. Though I’d chronicled plenty of morally compromised people—from Che Guevara to Andrew Jackson—these were different times. But if Takei’s name happened to be unfairly tarnished, as he claimed, should I add to his demise by deleting his story?

My publisher and I waited for the inevitable flood of #MeToo accusations against Takei, as they had with other accused sexual predators. But none came.

And then, as I obsessively read each new story, I noticed eyebrow-raising conflicting details in Brunton’s interviews.

Most prominently, Brunton didn’t appear to mention being drugged until two days after the THR story, following Takei’s public denial. And then, in a CNN interview, he confusingly didn’t recount any groping.

Social media and press had convicted Takei, but in the absence of more accusers, questions hung in the air: What exactly happened that night? And who was Takei, really?

So I resolved to find out more about what happened 36 years ago between two men late at night in an apartment, when no one else was around.

What I discovered after months of investigation—and after speaking at length with Brunton, people close to Takei, medical toxicologists and legal experts in sex offenses—suggests that this story needs to be recast significantly.

Brunton, a sympathetic and well-intentioned man, would go on to walk back key details and let slip that, in his effort to be listened to, he’d fabricated some things. This and other evidence would indicate a hard-to-swallow conclusion: We—both public and press—got the George Takei assault story wrong.

***

If Takei was the next Cosby, I was determined to out him fully. I interviewed friends and former colleagues about Takei’s private life. I spoke at length with people who used to frequent his old haunts in L.A.’s gay scene in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

This digging revealed no discernible trail of abuse—not yet, at least.

I left voice messages for Takei and his husband, requesting interviews. I contacted his publicist and social media team. One of his business managers eventually agreed to speak off the record but declined to comment further than Takei already had on Facebook. I asked Takei’s reps if he would be willing to apologize to Brunton for anything. They said that was unlikely and told me, Why apologize for something you didn’t remember and would never do anyway?

The other obvious step was to speak with Brunton. The finer details of his story could help reveal a pattern, if there was one, and clear up conflicts between the various news reports. Now 60 and happily married, Brunton was charismatic and forthright.

He agreed to let me tape our conversations and encouraged me to share them with Takei—hoping to jog his memory—and anyone else. We spoke for hours on the phone multiple times and in an email chain spanning several months.

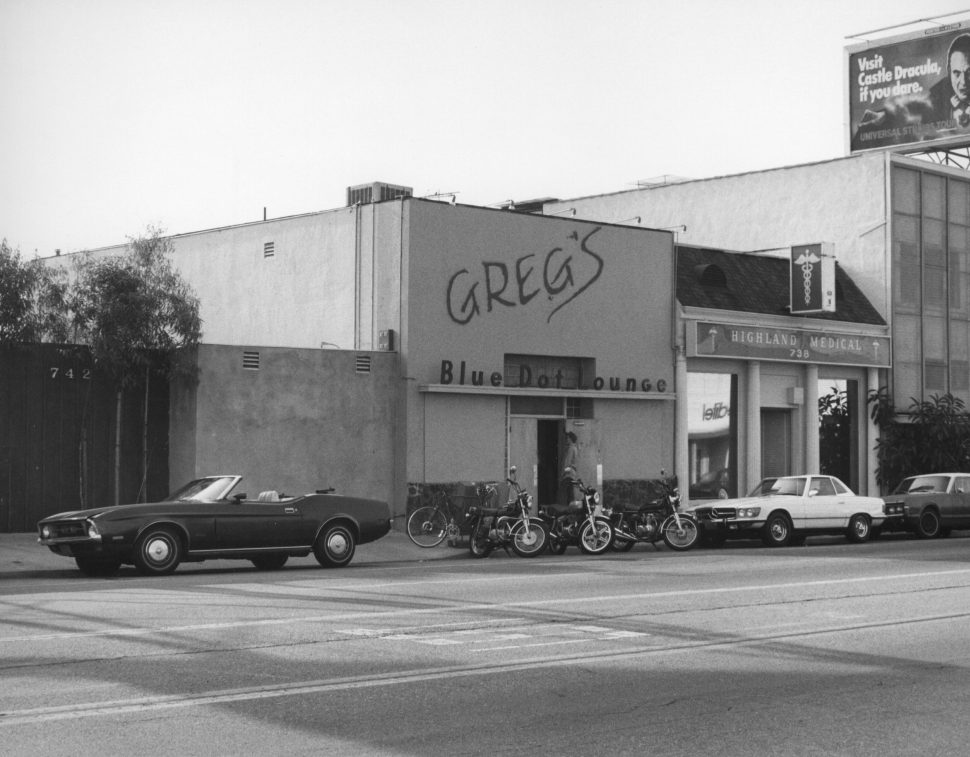

Brunton explained that he met Takei in the summer of 1981, while living with his first serious boyfriend, Jay Vanulk. They would hit L.A.’s gay bars a couple of nights a week. One was Greg’s Blue Dot Lounge, a safe haven at a time when many considered homosexuality deviant. That’s where they met Takei.

Brunton had not yet come out to his parents (and even had a female fiancée around this time). Takei, though he was not out to the public, frequented gay establishments and was supportive of other gay men. “He had a good sense of social conscience,” his Star Trek co-star Walter Koenig, who knew about Takei’s homosexuality early on, told me.

Brunton and Vanulk liked Takei and would chat on the nightlife circuit. “We weren’t friends for that long,” Brunton said. But, Takei “was very unpretentious. He’s not a typical actor, full of himself. He’s just really fun and nice.”

Brunton said the night in question began after he told Takei that Vanulk had ended their relationship. The actor, looking to cheer him up, took Brunton for a night out—dinner and wine and a play. Afterward, Takei invited the model up to his condo for drinks, and Brunton agreed.

Inside, the actor mixed cocktails in Star Trek glassware, which they drank while chatting. Takei asked if he wanted another, and Brunton said yes. “I was thinking, ‘God, these are strong drinks,’” Brunton told me, laughing.

After finishing the second drink, Brunton stood up from the couch and felt dizzy. Takei guided him to a bean bag chair, where Brunton lay down and “must have lost consciousness” for a moment, he said. He wasn’t sure whether he actually fainted or just experienced a brief memory brownout.

The next thing Brunton knew, his date was making a move on him. Brunton’s pants were around his ankles, and Takei was grasping at his underwear, Brunton said. Brunton protested, saying he didn’t want to have sex.

He said Takei was taken aback and replied, “I am trying to make you comfortable.”

Brunton did not believe him. He shoved Takei, telling him, “No.”

Takei was surprised. “Fine,” the actor said. He was not angry, according to Brunton. But, Takei said, “You’re not in any condition to drive.”

Brunton drove home anyway. “I sobered up and felt I could drive,” he told me. He didn’t pass out in his car and didn’t feel hungover in the morning.

So how did he feel the next day? I asked Brunton.

“Disappointed.

“I felt so privileged to know him [because] he was so nice, and a celebrity. I thought, ‘Well, he could be friends with lots of people, but he chose to be my friend.’ ”

Brunton’s voice got soft. “Do you see what I’m saying?”

***

The THR article implied that Takei had committed the criminal offense of sexual touching without consent. Twitter users read between the lines and accused the actor of drugging Brunton. Two days later, in an interview with The Oregonian after Takei issued his denial, Brunton said, “I know unequivocally he spiked my drink.” This was the first interview in which he was quoted saying he’d been drugged.

Brunton told me that it did not occur to him for a long time that Takei might have slipped him something.

“I thought it was just I was drunk,” he said. “I didn’t even start thinking that until years later when they started talking about date rape drugs. And, then Cosby and all.”

Decades after moving away from L.A., after he read media accounts of drink-spiked sex attacks and then the rape allegations against Bill Cosby, Brunton reconsidered that night. “Maybe I was drugged,” he concluded. “At 6-foot-2 and 180 pounds, I never had just two drinks and passed out.”

But for years, he questioned what really happened. “I’ll always wonder,” he said.

He gave me permission to share everything we discussed, so I took his question—and the symptoms he described—to two different medical toxicologists. What type of drug might Takei have used? I gave the experts the details of Brunton’s story (without revealing any identities to preserve the objectivity of their assessments) and asked for their conclusions on what drugs could have been involved.

It’s difficult to prove someone has ingested a date rape drug because such drugs typically leave one’s system quickly. Brunton did not see Takei add anything strange to his cocktail, though victims frequently do not notice such a thing.

To my surprise, however, both toxicologists immediately ruled out a spiked drink.

“The most likely cause is not drug-related,” said Lewis Nelson, the director of medical toxicology at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. “It sounds like postural hypotension, exacerbated by alcohol.” Postural hypotension is a sudden decrease in blood pressure that can occur when a person stands up quickly—and can make one dizzy enough to pass out even without alcohol. Brunton had made it clear to me, twice, that dizziness hit him only when he stood up.

Brunton’s description of “strong” cocktails suggests that they could have included two shots of liquor each, or about six ounces of booze in total, all consumed within an hour or so. He’d also been drinking wine earlier, a fact he apparently did not tell other reporters, which could have added to his blood alcohol content. (Additionally, it turns out that Brunton didn’t weigh the 180 pounds he’d initially told THR and me. “Actually, I was down to 170 then,” he conceded during our second conversation.)

A man of that weight in such a scenario could have registered a BAC of at least 0.10, making him legally drunk and prone to staggering, reduced motor function and slurred speech—and possibly worse depending on how much wine he’d had and how long it had been in his system.

“The alcohol alone, if drunk quickly, could account for [his browning out], particularly if there was a bit of postural hypotension,” said date-rape expert Michael Scott-Ham of Principal Forensic Toxicology & Drugs, a consulting firm in London, who has testified in criminal cases for 35 years. “To recover so speedily doesn’t sound like the actions of a drug.”

Even a mild dose of Rohypnol, or “roofies,” the most common date-rape drug, hits hard. It turns you into a rag doll with no control of arms or legs and no memory of several hours. Victims describe the next day as the worst hangover of their lives with a crushing headache, nausea and body pain. Someone who’d been roofied probably couldn’t have resisted a sexual advance, let alone driven home and remembered everything.

Other date-rape drugs also pack a punch. GHB has paralyzing and amnesiac effects. Quaaludes, the sedative that the recently convicted Cosby used to incapacitate women, causes a loss of muscle control that lasts for hours. Neither would have allowed Brunton to respond as he did, especially when mixed with alcohol.

“There are drugs today that may do this, but they did not exist [in 1981],” Nelson said.

I shared the toxicologists’ observations with Brunton, who admitted that this made him feel better. He was probably right all those years when he thought he was just drunk. He would still never know for sure, but, Brunton said, referring to Takei, “it makes him a little less sinister.”

Even without drugs, however, sexual touching without consent is a crime. On that part of the story, different publications reported slightly different versions as Brunton’s story changed over just a few days.

THR said that Brunton claimed Takei had been “groping my crotch and trying to get my underwear off and feeling me up at the same time.”

CNN spoke to him later—and Brunton’s account left out any touching: “He is on top of me and has my pants pulled down around my ankles and his hands are trying to get my underwear off.”

The Oregonian reported that, according to Brunton, “Takei was on top of him, shirt and shoes off. Brunton said his own pants were crumpled around his ankles and that Takei had his hand in his underwear, trying to get them off.”

To me, Brunton described slouching into the bean bag and then realizing his pants were down with the other man over him. “One hand is on my underwear, and the other hand is kind of like on my butt, trying to pull the elastics, you know? I mean, all of my weight is on the underwear.” He didn’t use the word grope and didn’t indicate that Takei had touched his genitals, either directly or through his underwear or had grabbed his buttocks. Unlike in The Oregonian account that reported a shirtless Takei, Brunton said the actor wore a short-sleeve T-shirt.

Brunton had said the same thing to all three outlets on one point: that when he told Takei that he did not want to have sex, the actor backed off and let him leave.

But what are we to make of the inconsistencies in these interviews?

Not recalling details like whether Takei was or was not wearing a shirt is a common example of the fallibility of long-term memory, according to neuroscientist and memory researcher Dr. Donna Bridge of Northwestern University. “Our memory is not built to remember precise details over long periods of time,” she told me. “We fill in the details.”

But if we are to believe the toxicologists’ assessment that Brunton’s drink was not drugged, the assault accusation hinges on him remembering having been groped, and on that element, his changing accounts might be more significant.

I asked him to clarify the issue. “Did he touch your genitals?”

“You know…probably…” Brunton replied after some hesitation. “He was clearly on his way to…to…to going somewhere.”

We shared a pause.

“So…you don’t remember him touching your genitals?”

Brunton confessed that he did not remember any touching.

***

The context of semi-closeted gay life in L.A. in the early 1980s goes a long way toward explaining how a man could get as far as taking down another man’s pants before realizing the light was red.

“ ‘Courtship rituals’ usually involved brief introductions, followed by going to one person’s residence with the ‘guest’ leaving after sex,” Edward Garren, a gay rights activist and historian who frequented Greg’s Blue Dot and other gay clubs in the neighborhood around that time, explained to me.

Someone young and new to this scene could certainly be surprised to learn that going out with a guy, then heading back to his apartment and having drinks together, would almost automatically be considered an invitation for sex in those days, according to Garren and others I spoke with who lived in L.A. in the early 1980s.

None of this would be Brunton’s fault. These kinds of things were not openly talked about much.

Context like this is extremely important from a legal perspective, explained former Senior Deputy District Attorney Ambrosio Rodriguez, who prosecuted rapists and molesters for decades in California. As with the toxicologists, I shared with Rodriguez the blind details of the scenario Brunton described to me.

“There’s nothing to prosecute here,” he explained, after asking detailed questions about the night’s alleged happenings. “People get drunk on dates and take off each other’s pants all the time,” he said. How this happens and what happens next is key from a legal standpoint, he explained. The crucial detail in the context of a consensual date with two adults who are drinking, he said, is that when the man who made the advance was denied consent, he backed off. “Making a move itself is not a crime,” Rodriguez said.

THR reported that four people who knew Brunton heard him tell the story over the years, but none were quoted and no details were offered. A possible explanation for that is how Brunton related what happened—as an amusing anecdote, rather than a life-changing trauma, according to Brunton himself.

For decades, he explained, his night with Takei had been a funny tale, “a great party story,” as he put it.

“I rarely thought of it,” he said. “Just occasionally, if his name popped up,” or if a Star Trek reference came up with friends. “I’d say, ‘Oh, well, I’ve got a story for you!’ ” he recalled, laughing. “They go, ‘Really? What?’ I’d tell people, and they’d go, ‘Ew!’ ”

He explained, “He was 20 years older than me and short. And I wasn’t attracted to Asian men.” He added, “I was a hot, surfer, California boy type, that he probably could have only gotten had he bought, paid for or found someone just willing to ride on his coattails of fame.”

The episode itself was “not painful,” Brunton said, chuckling. “It didn’t scar me.”

Even so, Brunton said he immediately revealed what happened to Jay Vanulk, with whom he was still “very much in love,” before he told anyone else.

Vanulk, however, contradicted Brunton’s account.

The two had continued to be friends after the breakup and even kept seeing each other after Brunton later moved back to the Portland, Ore., area. Vanulk told me the first he remembered hearing of Brunton’s encounter with Takei was when he saw it on the news in 2017.

“I know that we had met George Takei, but that’s about all,” Vanulk said. If Brunton had told him a version of the story in 1981, or sometime after, it hadn’t sounded dramatic enough for Vanulk to remember. He added that when he saw the news, he discussed it with Brunton’s ex-fiancée, Tracey, who told him she remembered hearing about Takei but did not remember any story of an assault.

These kinds of conflicting accounts—including Brunton’s own—are why the Northwestern University memory expert, Dr. Bridge, says, “Long-term memory should not be used as an accurate record of past events.”

“Our memories change when we recall them,” she explained, referring to decades of scientific research on the subject, “to fit the person’s worldview and mesh with experiences that happened after the event.” This is one reason why corroboration from people who victims spoke with immediately after an event is so crucial to making sense of old cases. And it’s how someone can think of an old memory as a “great party story” for decades and suddenly become upset about it in the context of Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby.

Brunton said that his anger toward Takei ignited in late 2017, after THR posted a story about Takei criticizing Kevin Spacey for deflecting a pedophilia accusation by coming out of the closet. “When power is used in a nonconsensual situation, it is wrong,” Takei said. The comment struck a nerve with Brunton. Takei was older than Brunton that night in 1981, and Brunton hadn’t consented to the come-on.

However, after his anger had died down, after he did all the initial news interviews, Brunton told me that he didn’t regard Takei as a criminal or an abuser. All Brunton really wanted, he said, was for the actor to say he was sorry.

And what exactly did he hope Takei would say, I asked?

“I just want him to apologize for taking advantage of our friendship,” Brunton said.

“You felt betrayed,” I offered. “Did you consider it an attack, at the time?”

“No,” Brunton said. “Just an unwanted situation. It’s just a very odd event.”

“If he came to you and he said…this was a misunderstanding,” I asked Brunton, “would you believe him?”

“Yeah, I would,” he said. “But I’d say, ‘Are you offering me an apology?’ ”

***

In the months following the THR piece, both accuser and accused experienced significant fallout.

Takei tried to fend off Brunton’s allegations with an emphatic denial, while stressing his record as an activist. “Those that know me understand that nonconsensual acts are so antithetical to my values and my practices, the very idea that someone would accuse me of this is quite personally painful,” he said in a statement. He was mocked by critics. Even people who believed Takei criticized him for the statement itself, saying that it hurt the cause of believing victims.

He also found himself scrambling to explain his participation in a Howard Stern radio bit from October 2017, about a month before the THR story—one of dozens of appearances on the show over the years—in which Takei joked with the shock jock about persuading shy men to have sex with him at his house. Takei apologized, writing, “For decades, I have played the part of a ‘naughty gay grandpa’ when I visit Howard’s show, a caricature I now regret. But I want to be clear: I have never forced myself upon someone during a date.”

Takei on Howard Stern in 2006. L. Busacca/WireImage for Sirius

It didn’t escape Takei’s notice that his political foes exploited the scandal. He tweeted that Russian propagandists had spread the news of Brunton’s accusations, citing The Alliance for Securing Democracy, a bipartisan advocacy group staffed by former intelligence agents that tracks Kremlin-influenced social media accounts. This backfired. Swarms of Twitter users and several publications scolded him. GQ (which I write for) posted the headline, “George Takei Says Sexual Assault Allegations Are a Russian Conspiracy.”

When I phoned Securing Democracy, a spokesperson confirmed that the propagandist network they track had indeed spread the THR story about Takei; it was the most popular article among the network at one point.

Newsweek, USA Today and other outlets included Takei in their lists of accused sex offenders like Roy Moore and accused workplace harassers like Charlie Rose and Matt Lauer. Takei’s run as the “moral compass of the internet,” as one blogger put it, was over.

Brunton was also attacked. Internet trolls found his Facebook page and left savage comments, driving him to tears. Strangers accused him of using the public accusation to promote his small business and mocked his artwork, which especially stung; Brunton had been a recognized as a talented artist for decades. (An archived copy of his high school newspaper shows that Brunton was named Best Artist in his Class of ‘75 senior superlatives. Despite Brunton’s earlier claim, those records do not indicate that there was an award given to anyone for Most Naive.)

And he was sad that Takei claimed not to remember him, even after they came face to face again in the mid ’90s in Portland, Ore.

Brunton had told THR that he found Takei’s phone number during his 1994 book tour for his autobiography and called, intending to confront him about that night in 1981. “We met for coffee,” Brunton said in the THR story, but, “I just couldn’t bring myself to do it.”

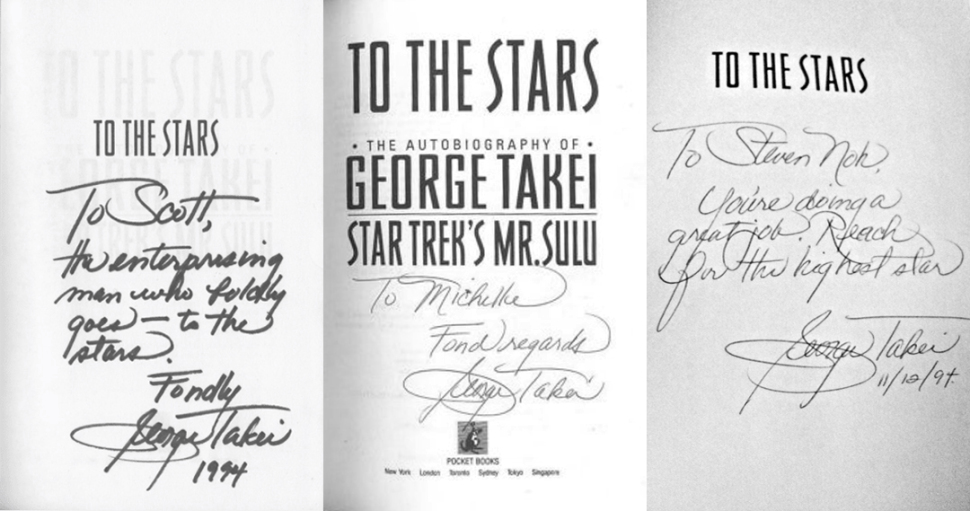

In one of our interviews, Brunton admitted that the coffee meeting never occurred. He said he actually just called Takei’s room through the hotel switchboard, and the actor had told him they could chat at a signing event for his autobiography, To the Stars.

When Brunton got to the front of the line of fans, though, he “chickened out” and did not confront him about their encounter.

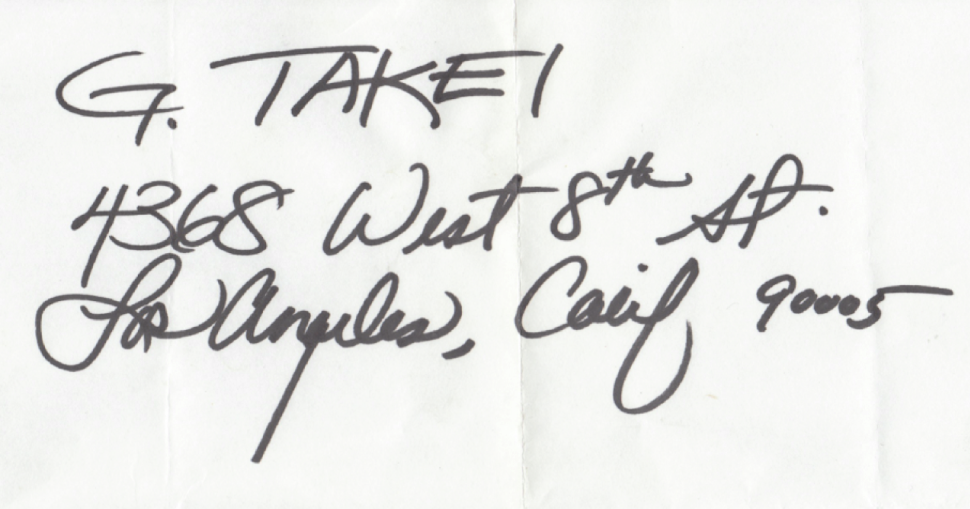

He got Takei to sign a book and write down his home address. Brunton shared photos of these with me, and the handwriting indeed appeared to match Takei’s. The inscription is similar to others Takei wrote in books on that tour, replete with Star Trek puns and the salutation, “fondly.”

At the time, Takei had been running his fan operation himself, no longer under the Star Trek franchise umbrella, largely out of his own home. He and the other nonleading cast members from Star Trek like Nichelle Nichols and Walter Koenig had only been paid for shoot days and two reruns for their work in the original series that ended in 1969.

In the early to mid-90s, each of these Star Trek alums was surviving from gig to gig, according to Star Trek historian Larry Nemecek.

This, along with the fact that the actor wrote his name as “G. Takei” and included his ZIP code—something most people don’t give a friend when asking them to come over—makes the note appear like a fan mail address:

Even if this had been an invitation to swing by, Brunton did not claim that the 24-year-old address was proof of an assault, as some people on social media implied. He simply said it was proof that 80-year-old Takei should remember him. “What’s amazing to me is he claims to have wracked his brain,” Brunton told me. In our interviews, he reiterated this frustration a half-dozen times.

Perhaps Takei would have remembered Brunton if the two had indeed sat down for coffee, as he claimed to THR. But they never did.

Meanwhile, at the time of this writing, the first search page of Google for “George Takei” contains headlines accusing the octogenarian of a sex crime that he claims to not remember, and his accuser admits to remembering imperfectly. The activist’s social media posts are now constantly met with replies from political opponents, accusing him of hypocrisy and rape.

“This has been the worst thing to happen to George since the internment camps,” a personal friend of Takei’s told me, asking not to be identified, for fear of being attacked online himself.

***

The New York Times reporter Emily Steel spent six months investigating the sexual misconduct accusations against Bill O’Reilly before publishing the story that eventually got him off of Fox News. Before his passing, my own mentor David Carr twice nearly exposed the Harvey Weinstein allegations and twice didn’t print what he thought he knew because he couldn’t confirm the whole story on the record. Ronan Farrow worked for 10 months before finally printing that story in The New Yorker.

These were massively consequential reports and pivotal to the ushering in of a long overdue era of justice for victims of sexual harassment and crimes.

But once that dam broke, the power of and interest in these stories has led to an incentive for the press to get them out quickly and for our polarized social media to quickly weaponize them. It’s easy to forget that every story has its own subtleties and nuances, and the consequences for getting things wrong can be severe.

These stakes merit taking our time and taking into account more than the typical web news report merits: things like number of accusers, corroborating witnesses around the time of the event, context, patterns of behavior, consistency and credibility of sources, and smoking-gun evidence (hush money, lawsuits, etc).

And in the absence of those things, when a “he said, she said” is left open to interpretation, the stakes necessitate taking into account the neuroscience of the fallibility of human memory and the psychology research that says humans are bad at reading each other’s intentions—especially when intoxicated. We owe it to both the victims and the accused to investigate all sides of a story before we unleash it for the masses to devour.

Experts estimate that only 3 to 5 percent of sexual assault accusations turn out to be untrue, while only 1 in 1,000 accused rapists end up in jail. Further complicating this, victims sometimes take back their accusations for their own peace of mind.

Now that we’re finally listening more to victims, we might risk not being able to finally punish the 97 percent who get away if we get act too hastily. Likewise, we’ll greatly disserve justice if we use rare, complex or unclear cases as an excuse to ignore or disbelieve accusers in other cases.

One activist I interviewed while writing this story told me, “If good people like George Takei get mistakenly swept up in the net of #MeToo, perhaps that’s a sacrifice they should be willing to make for the cause.”

Whether it’s appropriate to ask people to make those kinds of sacrifices should be up for debate itself. But one thing is clear: If we let the pendulum of justice swing too far and falsely equate lesser crimes or misunderstandings with more heinous sexual abuse accusations, such sacrifices can easily become moot anyway.

Whatever really happened between Brunton and Takei all those years ago, the meta-lesson here might just be that while our society has long failed victims of sexual harassment and crimes, correcting these monstrous injustices, while remaining ourselves just, will continue to be difficult.

I don’t fault Brunton for feeling wronged or for waiting all these years to cry foul. And just because he is inconsistent in his accounts does not mean we should jump to the conclusion that none of this happened at all. Victims often change details, out of panic or memory fallibility.

Neither do I fault Takei for feeling unfairly judged, or, at 80 years old, for not remembering Brunton.

But the question remains: What do we do with stories like this now?

“I don’t want to sound like I’m so vengeful, but, I mean, you do want to get back at someone like that that has done something like that,” Brunton told me. “If it just tarnishes their reputation a little bit, well, that’s what you get for doing what you did.”

What should you get for something like Brunton says Takei did? For making too bold a move on a date who, it turned out, just wanted to be friends? What kind of sacrifice should be asked for when an accuser feels hurt but says it all could be a misunderstanding?

Should your name go on lists alongside rapists and pedophiles? Should you lose your livelihood? Have your political voice muffled? Should the story of your human rights work be deleted from books? Should the accusation appear in your obituary?

Brunton didn’t really want all that; he says he just wanted to spur an old friend to reach out and to say sorry for an unwanted situation. The rest of those things are on us to decide.

Reporting and background check work for this story was done with assistance from The Hatch Institute, a nonprofit journalism foundation, with special thanks to editor Brad Hamilton.