If you’re a journalist, saying Pete Hamill helped you doesn’t mean that much. There are too many of us to count. And chances are you’re going to be well down the list of successful writers who, without Pete’s assistance, might not have gone so far. People like Carl Hiaasen, Nora Ephron, Mike Lupica, and Hamill’s brother, Denis.

Some of them gathered in December to tell stories about Hamill, who was featured in an HBO documentary. It was a heck of a celebration, an Irish wake of sorts for a legend who happened to be still with us at that time. The event, hosted by Glucksman Ireland House at NYU, had Pete seated in the front row with his wife, Fukiko Aoki, another journalist whose career he’s aided, smiling but probably squirming amid the waves of praise.

Well, count me among the legions who owe the guy.

This is my tale about Pete.

It features me as a young man, working my first paying newspaper gig, just like Hamill did at the New York Post 60 years ago, and what happened when he appeared on the scene. He didn’t do much, other than tee up the rest of my life. You have to wonder how often Pete has done this sort of thing, casually propelling an unknown into a winning trajectory.

—————

My story starts in 1986 in Mexico City the day after I graduated from college. A friend from Tufts had gone there, spent a year reporting, invited me to join him. Why not?

The city was reeling from the worst earthquake in its history, which struck eight months prior and killed 5,000. Hundreds of buildings collapsed, including a hospital and an apartment complex. The Mexico City News, where my college friend Mark worked, covered the quake’s aftermath with a ragtag staff of novices, trying to sort things out in print for ex-pats, tourists and locals learning English. Our editor, a smooth-talking American named Roger Toll, presided over the operation with genial detachment.

I worked the news copy desk, 7 p.m. to 11 p.m., with a half-hour break each night when the computer system had to be shut off or it would crash. Stories would come in and I tried to make them better. I battled a reporter with a habit of including information he himself didn’t understand. Some of us barely spoke Spanish. Many had only a rudimentary knowledge of journalism. Even so, we somehow stood as the most popular English language publication in the country.

My paltry hours of office obligation left plenty of time to report on matters that interested me, so I often took the opportunity, grabbed a notebook and set out to find a story. One day I covered a speech by the president of the country. Another I reported on people left homeless from the quake. Being on the streets revealed a sense of desperate energy to the city, the kind of focus that can follow a near-death experience. That summer Mexico hosted the World Cup, and late at night after the home team won a qualifying game, a throng of drunken celebrants encircled Mark and me in the middle of the city’s main avenue. “Que bailen los gringos!” they shouted. They wanted us to dance. So we did a jig. They went nuts. A guy in a grass wig brandished a ceramic jug of tequila. “Drink!” the crowd roared. We drank.

It was like being swept up by a national catharsis, an urgent need to shake off the horror of what had happened to their capital and rejoice over a soccer tournament.

In November, a buzz hit the newsroom. “We’re getting a new editor,” a reporter said. “And it’s Pete Hamill!” I didn’t know the name. Everyone else was impressed. We gathered for the announcement and to meet the incoming boss. Pete, I would learn, went to college in Mexico City on the GI bill, studying art back when he hoped to be a painter or maybe a professional cartoonist, and had returned years later to finish a book on Diego Rivera. That’s when this job opened up.

The departing Toll was as excited as a starstruck ingenue. He went on and on about Hamill’s famous ex-girlfriends — Linda Ronstadt, Shirley MacLaine, and yes, even the former first lady, Jackie Onassis, whom he met, and gave pointers to, after Viking handed her a book-editing job, as Hamill later told me. Pete looked put off by the fulsome introduction. “I’ve covered seven wars,” he said tersely, a not-so subtle rebuke. I studied his weathered face, his prize fighter’s posture, the cigarette dangling from his mouth and an untied necktie drooping from his collar. It all contrasted with Toll’s deep tan and dapper suit. “I think I’m going to like this guy,” I said to a colleague.

I did. We bonded over boxing, a sport he covered, and a love for newspaper work, which hooked me early. I’d edited the campus weekly at Tufts and freelanced for the New York Times as an undergrad, but what did I know? I was 22, in my first job, earning $65 a week, and a man I’d never heard of was about to become cornerman for my career.

How lucky was that? Here’s how: If I hadn’t gotten into the right cab, none of what follows would have occurred. This is the part of the story that I think about, and don’t like to think about. That things would have turned out very differently for me if not for the events of a warm evening in July of 1986.

——————

I had a night off from the paper and my friend and colleague, Ileana Tacou, requested I meet her at the News at the end of her shift. We were headed to the worst part of town.

Tacou had fled France and the reach of her wealthy book publishing family to work in our paper’s composing room, pasting together photos and copy. She also managed a house in Mexico City’s Polanco neighborhood where a number of us from the News lived, myself included. In her free time, she mingled with activists and former world champions.

When I told her I was a fan of the sweet science, she said in her heavy Parisian accent, “Well, if you really want to learn about boxing, you must come to Arena Neza.”

Nezahualcoyotl, or Neza, was then one of the world’s biggest slums, a sprawling post-war development of shacks on a drained swamp. About 1.5 million people lived there, the current size of San Antonio, most of them huddled in corrugated tin hovels, surviving without power or running water.

Many believed it to be the most dangerous place in Mexico. Its best feature was an arena where fans paid a few pesos to sit on bleachers and watch young fighters try to punch their way out of the ghetto.

“We’ll go together,” she said. “A friend will take us. Meet me at the paper at six.”

But when I showed up, she was nowhere to be found, so I hailed a cab.

“Where to?” the driver asked. “Arena Neza,” I said. He looked at me funny.

“I can’t,” he said. “It’s too far.”

“Well, can you take me at least part of the way?” I asked.

“I’ll drop you off at a bus stop. The bus will get you there.”

We rattled off. His meter wasn’t working. He pounded on it with his fist. The numbers started to spin. Then they went backward. “How much is this going to cost?” I asked. He told me we’d figure that out later. “Why in the world do you want to go Neza?” he asked. I explained about being a reporter.

Did I study journalism in school, he wanted to known. “Literature,” I told him.

“Oh. I love books,” he said.” What’s your favorite?”

“Dante’s `Divine Comedy.’”

“Me too!” he said. “That’s a great one. How’s it go again?”

How’s it go again? Let’s see now. I told him the author, Dante, meets a famous poet, Virgil, who gives him a tour of the afterlife, where he sees all these dead guys being tortured. I had to reach for my pocket dictionary because I couldn’t remember the word for sin.

I stumbled through the plot, relating punishments for the gluttons, the greedy, the murderers. The driver seemed enthralled.

“How much farther?” I said.

“Still a ways to go,” he said.

I continued. But it seemed we were approaching our own version of hell. I saw row after row of shanties, lined up along shadowy dirt paths, people milling about in rags, spread out for miles in every direction. It was an epic wasteland of hopelessness.

“We’re here,” the driver announced.

“OK,” I said. “Where do I get the bus?”

“No,” he said. “This is the arena.”

He couldn’t be right. We had stopped in front of a small white concrete building with narrow windows and a rusted over Corona sign. At about three stories high, and taking up only part of a block, it looked too small for any kind of sporting event. A crowd had gathered at the entrance.

“How much?” I asked my driver. The meter read 2,345. We’d been going more than an hour. I had about $10 worth of crumpled up pesos.

“You know what?” he said. “This one’s on me. I enjoyed our conversation.” I tried to hand him my money. He refused.

Don’t let anyone tell you that a degree in English can’t come in handy. Or that an appreciation of fiction plays no role in getting ahead, something I would find out soon enough.

As oddly gratifying as the trip had been, I was no less surprised to find Ileana standing just a few feet away from the cab.

“What happened?” I demanded.

“I couldn’t find you so I left. Come quick. I have your ticket. The first match is about to start.”

——————

It was a grudge match, she explained.

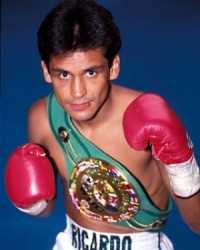

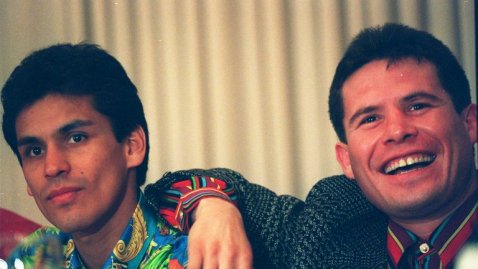

The bout pitted a young riser, Ricardo Lopez, 20, who many believed had a shot to become great, against Herminio Ramirez, an arch rival the same age who’d beaten him out to represent Mexico in the 1984 Olympics, according to Ileana. They were members of the strawweight class, or mini mosca, meaning no more than 105 pounds. It’s the lightest division in boxing.

“Lopez is better, but Ramirez had pull on the Olympic team. He knew somebody. It’s politics,” she said.

The two entered the ring. Lopez’s remarkably small hands, with red leather gloves on, seemed about as menacing as Christmas mittens. Ramirez wore a scowl, the face of a street brawler.

The bell rang and a flurry of punches followed. The hand speed of both fighters made it difficult to be sure which blows landed and which missed. Ramirez grimly marched forward, chin down, while Lopez darted in and out, fluidly weaving and avoiding punches. I thought Lopez won the first four rounds, though it was close. I found myself rooting for him.

At the final bell both raised their hands in victory. Lopez won a unanimous decision. It was his ninth victory as a pro.

“That was impressive,” I told Ileana. “I’d like to get to know these guys, maybe write about them.”

“It shouldn’t be too hard. They all train at the same gym, Baños Lupita. If you want, go there and see if they’ll talk to you.”

The gym was near the city’s center in a modest colonia, which, compared with Neza, might as well have been Acapulco. It was probably the most successful boxing gym in Latin America. You couldn’t go 10 paces without running into a world champ, current, former or possibly future. The day I arrived it sounded like someone was shooting off a .357. Boom! Boom! Boom! In one corner, by himself, a lanky man in shorts blasted a heavy bag with savage left hooks.

“Who’s that?” I asked a guy with a mop.

“That’s Cañas,” he said.

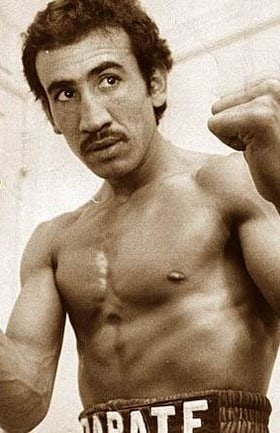

The nickname orignially referred to a cane or reed — the boxer banging away was thin, with whip-like power — but now it took on a slang meaning: white hair. Carlos Zarate was 35 and attempting a comeback, seven years after he’d quit, and though his hair remained ink black, many considered him past his prime. Zarate had piled up enough knockouts as a young man, including a record 20 in a row, for the Associated Press to proclaim him the best bantamweight of the 20th century. Even so, nobody gave White Hair a chance in his return. I wasn’t so sure. I couldn’t imagine being on the receiving end of those hooks.

On my third visit to the gym, Lopez turned up. I told him I enjoyed his fight at Neza and he grinned bashfully. “Thank you very much,” he said. Did he have designs on a title? “Oh, yes,” he said. “I have to train very hard and I can’t do bad stuff,” he said. “All these fighters, something always gets them. It’s the booze, or the women or the drugs or the gambling.” He pretended to smoke a joint, then waved his arms across his chest like an NFL ref signalling incomplete pass. “I’m not going to do any of that.”

After his workout, we took a walk. This kid was all kid, prone to re-enacting scenes with dramatic flair, laughing heartily, doing impressions of boxers who’d fallen to pieces. “When I get to be champ, I’m going to save all my money and buy a big house and take care of my family,” he said.

I decided to join the gym myself. It cost all of 10 pesos. This allowed me to get to know the crowd better, so I put on gloves and learned how to throw a crisp jab. I took a liking to Zarate, a legendary Lothario, who wasn’t much to look at, with a wide smashed nose and ears that stuck out comically. That didn’t hurt his chances with the ladies. I asked how many children he had. “In which neighborhood?” he responded.

I enjoyed getting to know Lopez. His boyish enthusiasm seemed at odds with his profession, which I knew to be crawling with crooks. He brought me to his house, where I met his mother and uncle and siblings. The uncle owned what Ricardo called a jewelry store but was more a rolling cart with an assortment of gold-plated items and an old engraving machine.

One day he dashed behind the machine. “Don’t watch what I’m doing!” he ordered. He came around and smiled in my face. “I have a present for you,” he said. He held out his palm, and there was a minuscule gold boxing glove. On the back of it he’d inscribed the letter “B.”

—————

I felt ready to write about him. I sat down at my terminal and tried to think of a good lead. I went for the one-line teaser: “Ricardo Lopez doesn’t cuss.” Nor did he drink, smoke or gamble, I wrote. I tried to convey his childlike glee, his plan for world domination, his speed in the ring, his deft defense.

It felt like I’d done a decent job but I am never sure about my own writing. I didn’t include anything on the back story, how I happened to have seen his fight, but knew that if I hadn’t made it there, if weren’t for the cabbie who took me all the way to Arena Neza and didn’t charge me, I couldn’t have done this piece.

I passed the story along to our sports editor, Luke Betts, and he promised to give it good play.

The next night at the paper, just after my editing shift had started, the phone rang. “Pete wants to see you,” his assistant said. Had I done something wrong?

I went into his office. Pete was holding the paper open to the sports section. “Great story about Lopez,” he said. “Thanks,” I said. He gently chided me for not including more of the fighter’s record as a pro but said I did a good job describing him. “You like boxing?” he said.

And so it began with Pete. I learned he knew quite a bit about sports, along with politics, books, film, music — one of the best read, most widely knowledgeable people I’ve known. He had a particular fondness for boxing, and it was a fine time to be on that beat. Zarate, Lupe Pintor, who was teaching me how to throw hooks, and another ex-fighter on the scene, Ruben Olivares, are regarded as being among the top Mexican pugilists of all time. Also in that group was Julio Cesar Chavez, a champ already and still climbing, who turned out to be as good, if not better, than all of them.

Being that involved with fighters opened the door for me with Pete, who had written extensively on the sport. He asked my opinion on how we covered stories at the News, what I thought of the strengths and weaknesses of our staff. And he gave me assignments. Once he sent me to a luncheon gathering of lucha libre stars, the colorfully costumed grapplers Mexicans love. I saw one wrestler duck his head down under a tablecloth so he could pull off his regular mask and snap on an eating mask. Pete thought that detail was hilarious.

Another time I did a story about hanging out with Olivares, who spent the day driving around town in his van, smoking pot and cracking jokes with his pals. When they dropped me off, a thick, pungent cloud poured out of the vehicle, a scene straight out of a Cheech and Chong flick.

In addition to sports, I covered breaking news and wrote a city beat column. And I stayed on the boxing beat. Pete sent me to New York, where my mother lived, to cover Chavez’s next title defense. The day after he won a lackluster decision over Puerto Rican Juan Laporte, earning boos from fans at Madison Square Garden, I knocked on the fighter’s hotel door and we talked for an hour, Chavez stretched out on his bed, walking me through each round of the match. It was the sort of close-up, relaxed encounter that doesn’t happen much these days in sports reporting, and I got to be there because Pete trusted me to come up with something good on an emerging national hero.

Prior to the 1987 Super Bowl, with his hometown Giants facing the Broncos, Pete and I put together a pull-out section for the paper on the event. This was a special assignment, a chance for me to work with him on a project that the paper was going to promote and would likely be a hit with readers. He asked me to write a think piece about why the game itself so often stunk. On the big day, it looked bad for the G-men. And then, improbably, they fought back and won. Pete was ecstatic. The headline he picked: “GIANTS!” Peering over the page proofs, Pete marveled that his star-crossed team had finally won a Super Bowl. “Some days you want to live forever,” he said.

Our ride at the News didn’t last nearly long enough.

—————

In February, three months after Pete became editor, a battle erupted over a front-page story in our paper. It involved protests against a newly proposed tuition at the city’s big public university, UNAM, which previously hadn’t charged to enroll. The move outraged students, who staged a strike. Then a group of demonstrators traveling by bus to a rally came under attack. Someone pulled out a gun and blasted their vehicle.

No one was hit, but the shooting was considered an ominous development for a country with a Kent State-like massacre, when as many as 400 students were shot dead on campus in 1968.

We ran a photo of the yellow bus and the headline, “Gunshots rip protesters’ bus.”

The publisher wasn’t happy.

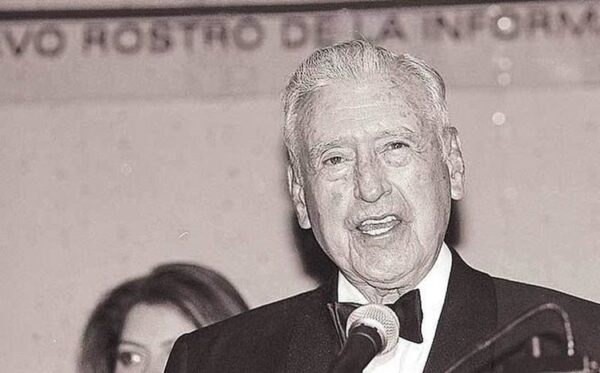

“Don’t you know that we’re on the side of the administration in this?” Romulo O’Farrill Jr. raged at Pete. O’Farrill, chairman of the publishing and television conglomerate Televisa, was used to getting his way. Nor was he a stranger at the offices of the News, a sister paper of his Novedades chain.

Pete tried to reason with him. “I happen to agree,” he told O’Farrill, saying he felt there was nothing wrong with a struggling university imposing a modest fee to improve its finances. “But we’re a newspaper. We have to cover both sides.”

The publisher issued an ultimatum: either you ignore the students or you leave. Hamill’s indignant response: “Ya me voy!” — I’m gone. He stormed out of his office and came straight to the newsroom to tell us what happened.

We staffers were stunned. Our editor had been asked to accept self-censorship and refused. We huddled to discuss what to do. For most of us, there wasn’t much to decide. In all, 13 reporters and editors quit in solidarity, knowing there was no point working for a paper if the man paying the bills dictated your stories.

Our mass resignation, a slap in the face of one of Mexico’s most powerful companies, became a story. We were interviewed in print, TV and radio. The New York Times ran this Reuters piece. Some of us wondered if there might be retaliation. All I knew, I was out of a job. So I said goodbye to Pete, unsure if I’d see him again, packed up and went traveling across Mexico. I had $250. Back then it was more than enough.

——————

Two months later I was on the beach in Oaxaca when I got word from David Bennett, a friend from the News who’d moved to New York after our exodus, that Pete had returned to the city and helped David get hired on the copy desk at the Daily News.

“You should probably come up here,” he said.

Seeing as how I was down to my last few pesos, I figured it was time to wrap up my Mexican adventure and face reality. My mom said she’d let me crash on the couch of her apartment on East 49th Street in midtown, so I’d have a place to stay while getting settled. And I’d have Pete. New York can be tough on newcomers but less so with an icon on your side.

I found that out within a week of my arrival when Pete invited me to have lunch with him and Jack Newfield, the famed muckraker and one of Pete’s best friends. We spent two hours debating who was the best fighter, pound for pound, in history. They both wrote for the Village Voice, and Pete had a current assignment there, a cover profile of the Mets first baseman, Keith Hernandez. “Come down to the paper and I’ll introduce you around,” he said.

He did, and I ended up with a story from the sports editor, Michael Caruso. It was a feature on Puerto Rican fighter Edwin Rosario, who was managed by Mike Tyson’s team, after Cus D’Amato’s death, and was not happy about playing second fiddle to Iron Mike. At the Voice office I saw Pete staring at his screen. He was stuck trying to describe how easily and expertly Hernandez fielded his position. “He plays first base like he’s…???” Pete said. “Like he’s going for a morning stroll?” I suggested. Pete typed that in.

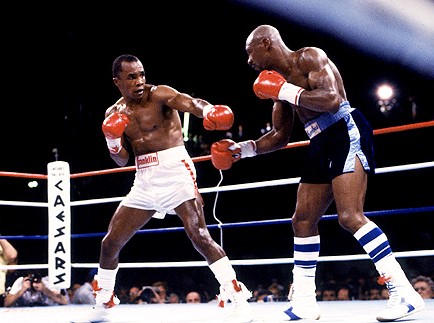

I was with my mom at her apartment a few days later when the phone rang. “What are you doing tonight?” It was Pete. He wanted me to join him for steak at Gallaghers on West 52nd, then after we’d walk across the street and watch that night’s fight on closed circuit at the Roseland Ballroom. It was destined to be a classic, Sugar Ray Leonard versus Marvin Hagler.

And so it was that after having been in New York for all of one month, I found myself at dinner surrounded by legends: Bob Fosse, with a blonde date about 30 years younger than himself, and the actor who played him in “All That Jazz,” Roy Scheider. There were two famous authors, Gay Talese and Peter Maas, along with Pete.

His piece about Hernandez had just come out, and he told the table a story about being at Shea, after the Mets acquired their Gold Glove MVP, and watching him step to the plate. The trade was fortunate for Hernandez, who left behind a scandal in St. Louis, where he’d snorted “massive amounts of cocaine,” as the player himself would later admit.

Pete noted that when Hernandez entered the batter’s box, a loudmouthed fan with “leather lungs starts yelling, `Hit it down the white line, Keith!’” Everyone cracked up — other than Fosse’s girlfriend, who rubbed her nose nervously, then darted off to the bathroom. Just like in the movie, I thought.

“I was a boxer but I only ever had one fight,” Scheider confided to me, while his tipsy wife slung her arm around my shoulder. “I was nervous as hell. I kept watching the other guy’s shoulders and arms. I just didn’t want to get hit. And then, bam, he punched me hard, right here.” The actor pointed to his famously crooked nose. “Broke it right away. That’s how I got this.”

As we watched the fight, Scheider kept leaning over to tell me how it was going. “Hagler won that round!” he announced. I liked both fighters but preferred Leonard, who won a split decision. Some aficionados have called it the greatest boxing match ever. Certainly it was a highlight of my early days in New York. Did I mention Pete paid for everything that night?

My own piece was published in the Village Voice, and I started to pick up freelance work. In September, David told me the New York Post was looking to hire someone for a features job. He’d suggested my name to the editor, Pucci Meyer, who knew Pete. “I’m sure he’ll put in a good word for you,” David said.

Pucci was a delight. We met at her office. “So you worked with Pete?” I asked. Meyer, who had won a Pulitzer as part of a Newsday team probing the French connection heroin scandal, went on to edit the Daily News magazine, which published fictional short stories by Hamill. “Pete wrote one a week for a year,” she said. “I don’t know how he kept it up.”

I got the job, helping Pucci and a young staff reporter put together sections on education, health, food and other subjects, but also working on the side for the city desk. That began a lifelong association with the Post, during which I served full-time and part-time, off and on, in different roles. The investigations unit I led, starting in 2001, published front-page exclusives, an experience that paved the way for heading my own foundation.

“Why do you want to work at that terrible paper?” asked my mom, a devoted liberal, not long after I was hired. I understood her point. It would not be the only time I faced that question, including from staffers at the Post. “Maybe I can make it a little better,” I offered. If it once was good enough for Pete, I said. Plus, they paid well.

But I was on a break from the Post in 1993 when Pete became editor and the paper declared bankruptcy — and he famously led a rebellion against the new owner, Abe Hirschfeld.

Hirschfeld, the day after a court handed him the reins, fired Pete. Or tried to, anyway. Pete refused to go. He set up shop at a diner in the paper’s building on South Street, holding meetings and planning pages, then oversaw an edition that attacked Hirschfeld. The wacky publisher, a Polish-born parking garage magnate who later went to jail for trying to assassinate his ex-business partner, got savaged over 16 pages. One headline asked, “Who is this nut?” The assault in print wasn’t just a personal thing. Pete was trying to save the paper that had given him his start.

It worked. A judge ordered Hirschfeld to reinstate Pete, and he got a hero’s cheer when he returned to the newsroom. The episode led to a cringe-inducing photo of Pete, who was captured trying to wiggle free when Hirschfeld grabbed him and kissed his cheek. The coverage, on St. Patrick’s Day no less, went national. It was a reprise of sorts of what went down in Mexico.

———————-

We were no longer working together, but Pete and I stayed in touch, and he continued to make me a part of his ever-widening circle.

He invited me to his reading group, which met every month at his apartment in the West Village and included Richard Price, who wrote “Clockers” and the screenplays for “Sea of Love” and “The Color of Money,” and Richard Emery, a top civil rights lawyer. The celebrity of the group was Emery’s willowy wife Lori Singer, the blonde actress who starred in “Footloose.” Two other participants, Charlie Sennott and Mark Kriegel, had reported for the Post and wrote books, guided all along by Pete. We’d sit around and hash out views on novels and short stories. “Nobody dared to call it a book club,” Sennott said.

Emery later divorced Singer in a tangled and absurdly expensive split, which I wrote about, at the lawyer’s suggestion, as part of a series I did investigating corruption among Manhattan Supreme Court matrimonial judges, which the FBI was probing. It was the kind of expose the late Newfield would have loved. He had pioneered “The Worst Judges in New York,” which he developed at the Voice and later took with him in stints at the Daily News and the Post.

David and I went to visit Pete at a farmhouse he bought in upstate New York. One night he gave us a tour of the barn, which he was turning into a giant library. He’d accumulated thousands of books and didn’t have a proper place to store them all. That library was like a symbol of Pete’s life, an old and beautiful place where Pete could retreat, surrounded by great writing. I remember stopping in when he gave a lecture at St. Francis College, where he talked about having had a Brooklyn public library branch near his boyhood home and how that altered the course of his life. He then launched into such a passionate endorsement of “Moby Dick,” I could imagine students in the audience rushing home to start reading the novel right away.

If you ever went to Pete’s home and happened to mention you were working on a story, chances were you’d leave juggling an armload of books on that subject, loaners from Pete’s personal library. Pete was always suggesting writers I should try. I’d never read Irwin Shaw until he told me to check out Shaw’s collected stories, which includes some of my favorites by any author, gems like “The Man Who Married a French Wife.”

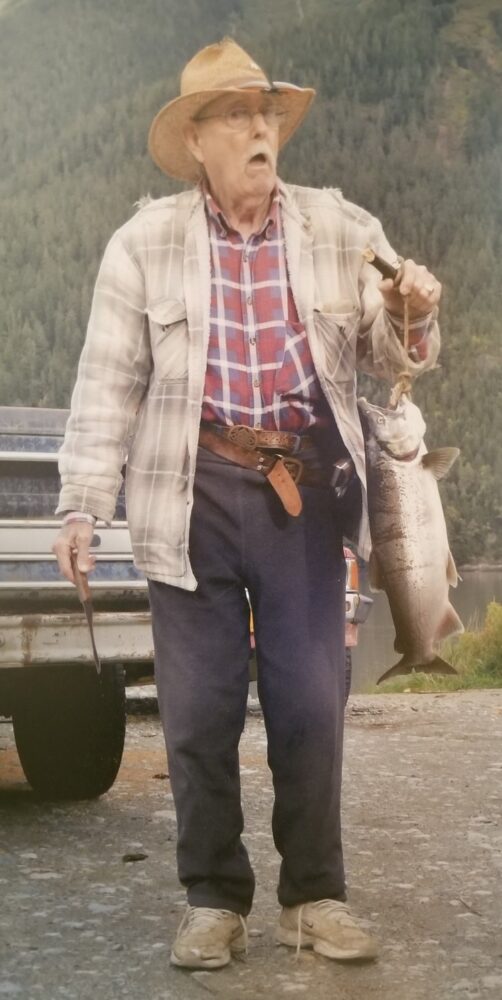

His own best-seller, “A Drinking Life,” came out in 1995, and I had my copy on a coffee table at the apartment in Carroll Gardens where I lived with my girlfriend Amy when her father Bill came in from Alaska to visit.

He was known as “Wild Bill” — a laconic World War II vet who’d landed at Normandy, shot at Germans in the French hedgerows, and nearly froze during the Battle of the Bulge. He got the nickname after he and Amy’s mom split, and he moved to Hyder, Alaska, living in a trailer, drinking whiskey at a local saloon and carrying a revolver as he fished for salmon on the banks of a nearby river. The weapon came in handy when a bear showed up and tried to steal his catch. The bear was persuaded to look elsewhere.

“What’s this?” he asked as I was leaving for work. He was holding “A Drinking Life.” I knew Bill had grown up in Brooklyn, not far from where Pete was raised. “You might like that,” I said. “It’s good. It was written by a friend of mine. There’s a lot of great stuff in there about Brooklyn in the 1940s and ’50s.”

That night, when I walked in, I came face to face with Bill, who had downed a belt or two before my arrival, staring at me with fire. “You see that Pete Hamill again, you tell him he’s a son-of-a-bitch,” he said.

“Why?”

“He made me cry.”

—————

In early 2014, Pete almost died. I learned this from his brother Denis, who wrote a column for the Daily News that sometimes turned autobiographical. When it did, he referred to himself as Ryan.

In this case, his piece was about Pete, whom he called “the patient.”

A cataclysmic mix of ailments combined to nearly take him out. Pete had returned from a trip to Italy with Fukiko, not feeling well. She took him to a hospital in Manhattan, where he collapsed, possibly from a stroke, or series of mini strokes, his doctors believed. When he fell he broke both hips. He was also suffering from kidney problems. He was touch and go, languishing in a coma, until he finally awoke.

I went to see him. He was still groggy — and quite uncertain as to what happened. “We just don’t know,” he said. One other bad outcome: when Pete went down, his glasses broke. And because he didn’t have a prescription on file, no one knew what numbers to use to make him a new pair. “Now I can’t read,” he said.

He was soon transferred to a facility in Cobble Hill, not far from where I lived. So I went to my optician and told him I hoped he could solve the glasses problem. It turned out this guy grew up near the Hamill family and knew all about Pete and his brothers. He promised to do what he could, sending me off with a variety of different reading glasses to try out and arranging for his assistant to check on Pete.

There was only one, admittedly selfish upside I could see to his current condition. You could go see him. Being Pete’s friend means having to compete with a cast of thousands. By no means are you the only one who wants his time. But as he convalesced, Pete was stuck, with not much to do. I went as often as I could.

And he never seemed down. One day he told me he was sorry, but the vintage Brooklyn Dodgers cap I’d given him was gone. He’d been wearing it around Europe but had forgotten the cap under a hotel bed in Italy. Even so, he was tickled by the thought that some lucky Italian kid might have found it — and would proudly don a cap of Dem Bums with that blocky “B” logo the team wore back in 1911.

One excursion with Pete included a friend from the Post, Myron. We stopped for a bite at Walker’s in Tribeca, sitting at an outdoor table on a fine afternoon. Just around the corner was where JFK Jr. lived before his plane crash, and I remembered Pete once told me that Jackie never bought the lone-gunman theory about her husband’s murder. “She thought it was a combination of the Cubans and the mob,” he said. I ducked inside and a waiter nervously approached. “Is that Pete Hamill?” he asked. He happened to be reading Pete’s “Tabloid City,” and had it with him in his bag. “Do you think he’d mind autographing it?” Pete was happy to accommodate. Myron, also mentioned in the book, opened it and pointed to his name, then signed as well.

I asked Pete if he would be up for giving me a hand with the investigative journalism foundation I’d been running. “Sure,” he said. “Only I don’t want to go to any board meetings.”

“Neither do I,” I said. “Don’t worry. I just want your thoughts on stories we’re going to publish.”

Of course he helped. He joined our board of advisers. His critiques were pithy. Of an enterprise piece he just said: “It’s too long.” Our first story ended up winning a national award.

During another visit Pete worried me. He looked out the window and said, “All my friends are dead.” He did so matter-of-factly, an observation, not a maudlin regret. He didn’t mean people like me, those on the periphery, but buddies who were with him early and knew him best. Writers like Newfield and Jimmy Breslin. Guys he covered and admired. The lightweight champ Jose Torres and his trainer, Cus D’Amato. His ex, Jackie O. And three who were with us that night at Gallaghers: Scheider, Fosse and Maas.

——————

My own circle is filled with people I met through Pete or who worked for him or both. Walter, who was on the copy desk at the News, has been a close friend for three decades. When the documentary aired, I got flooded with requests from those who’d been around Pete but lost touch. Did I know how to reach him?

I didn’t fully realize it until I started writing this, but I’ve modeled my working life after Pete’s. Reporting, writing, reading. Sticking it to the powerful. Sticking up for the little guy. I’ll never be as famous — that’s rarefied air Pete occupies. And I can’t possibly match his accomplishments. But I take pride in trying to help others, some of whom have achieved admirable things, and being a good friend.

My father died when I was a teen, so I didn’t have a male role model at home. You could do a lot worse than Pete Hamill.

—————

The other night I went into my office and opened a small box. Inside was a tiny gold boxing glove, now a bit tarnished. I squinted my eyes and could make out the engraved “B.” I hadn’t thought about that wide-eyed kid, Ricardo Lopez, in years.

You know what? Everything Lopez told me he wanted to do, he did.

He did, in fact, become a world champion, then defended his title a record 21 times. When he retired in 2001, he left never having lost as a pro or amateur. He’s as good as any Mexican fighter who stepped in a ring. Many experts think Lopez was the best strawweight in history.

Some even put him in the mix for best fighter of all time, regardless of class, including ESPN’s Max Kellerman, who said he would group Lopez and five others — Bernard Hopkins, Shane Mosley, Roy Jones Jr., Floyd Mayweather and Marco Antonio Barrera — “up against the top half dozen pound-for-pound fighters from any era you can mention.” Lopez, he wrote, is “perhaps the most picture-perfect fighter I have ever seen at any weight.”

He also saved his money. He became a father — his son, Alonso, also a boxer, went 15-0 as a pro. Lopez now works as a boxing commentator for Televisa, the same outfit Pete told off 32 years ago.

And that little glove of gold he gave me? It’s among my favorite possessions, an emblem of a turning point for me and a reminder that some of the best journalism comes from getting close enough to people so you can tell their stories with empathy.

Then I watched the film about Pete and his late friend, “Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists,” and felt the full weight of gratitude. Not just for all that he did for me. But for the way he pursued his craft, how the documentary captured his approach to reporting so that viewers who didn’t know Pete, who never saw him in action or never even heard of him, could glimpse his greatness.

And know that he had a profound impact on the city of New York and the journalists who followed him.

It was a joyous moment, a mix of pride I felt for Pete and thanks to the fates for having gotten to meet him so long ago. It reminded me of his exhilaration in Mexico when the Giants finally won the Super Bowl.

Back then he’d said it just right.

Some days you want to live forever.