A flurry of credible misconduct allegations has brought national attention to the sexual harassment many women face on the job, but there’s been little progress on another workplace challenge: what they earn compared with male counterparts.

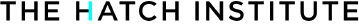

Although women hold half of all government jobs, they make 10 percent less than men in the public sector, according to data on the median income of state and federal employees obtained by The Hatch Institute.

In addition to this pay gap, men comprise 73 percent of civil service workers who earn $100,000 or more each year, the figures show.

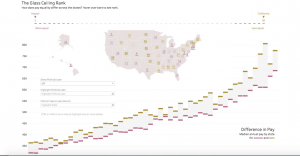

The foundation for investigative reporting used freedom of information requests to collect salary records from all 50 states and most federal agencies, leaving out the Department of Defense and a handful of others that did not provide the names of its workers or demographics.

The result is the most comprehensive look in history at how our government pays its employees.

As with private companies, the pay imbalance was particularly stark in public service professions where men dominate, such as law enforcement, engineering and technology. These jobs in general offer higher salaries than sectors such as education and healthcare, which employ more women.

At the National Science Foundation, for example, men make $40,000 a year more than women in median income. At the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board, the disparity is $70,000, or a 42 percent pay gap. Similar gaps were found in varied offices such as public safety regulators, the Department of Agriculture, the Commission of Fine Arts and the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

“We need to raise the floor and increase the value we place on certain areas, in particular jobs like healthcare and education that women make up traditionally,” said Latifa Lyles, director of the Women’s Bureau at the Department of Labor.

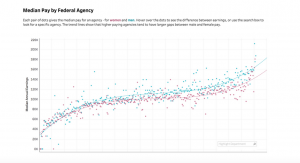

The state with the largest discrepancy between men and women is California, where male workers make $19,500 per year more in median income than their female colleagues, a 24 percent pay gap.

Salary expenditures in law enforcement revealed one facet of the problem. The 8,552 men employed by the state’s Highway Patrol earn twice as much as women there, $115,000 to $57,000. Most of the officers in the department, which employs more cops than any state other than Texas and spends more than $1 billion a year on salaries, are men.

And their compensation surpasses wages for administrative or clerical work, roles mostly held by women. In some cases, female Highway Patrol office supervisors earn less than their male officer subordinates, according to the documents.

A similar wage gap exists in the California Department of Corrections, one of the state’s largest employers and an agency mostly staffed by men.

“Our issue is not a pay gap, it’s a gender distribution gap,” said Joe DeAnda, the former director of communications for the state’s Department of Human Resources, noting that California law mandates rigid pay scales, with little room for managers to reward their best workers beyond set salary ranges.

Left-leaning states tend to have greater pay equality than those with predominantly conservative leaders, but there are notable exceptions. While California ranked last for pay equality, Texas ranked ninth. Hawaii and Maryland nearly reached gender-neutral compensation, as did the U.S. Postal Service, which showed only a 2 percent pay gap.

It’s worth noting that the federal government’s track record on equal pay is likely worse than these numbers indicate.

That’s because its statistics do not include data from the Department of Defense, whose 1.3 million active service men and women and 742,000 civilian personnel make it the nation’s largest employer. Men hold many of the highest profile positions at the Pentagon, which has never released demographic information about its workforce.

In rejecting Contently’s Freedom of Information Act request, a department spokesman said the agency was entitled to an exemption that permitted it to not have to disclose its members’ names, genders, ethnicities or other factors. No state or other federal agency claimed to have such protection.

Closing the pay gap has confounded both the public and private sector, where the difference in gender compensation is about 20 percent, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, a nonprofit thinktank.

The federal government has endorsed fair pay since the 1960s, when John F. Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Act, but it has struggled to meet that goal partly because of how it manages its workers.

In entry-level positions, the records show, the federal government has largely succeeded in hiring diverse workers across gender, age and race. But it has promoted relatively few of these workers to supervisory positions, preferring to bring in administrators from the more homogeneous private sector, analysts said.

“We talk about hiring people from within, developing your current talent,” said Cynthia Ferentinos of the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, a federal agency that wrote a 2011 report on the problem.

“There’s a lot of diversity at the entry level, and you can take advantage of that when promoting for the higher level,” Ferentinos said.

The Trump administration is a practicing example of gender pay inequality.

The difference in earnings between male and female White House staffers has more than tripled during the first year of his presidency, according to an analysis by economist Mark Perry of the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. The median female salary of White House employees is $72,650, while the median male salary is $115,000.

“This sends all sorts of bad signals for pay equality,” said Emily Martin, a lawyer at the National Women’s Law Center. “And Donald Trump has not shown interest in addressing these issues.”

Not only do women get paid less in the Trump White House, Trump’s cabinet also has the fewest women of any cabinet in 35 years.

Fair-pay advocates like Martin fear that the Trump administration is reversing gains toward pay equality in the private workforce as well, pointing to it having scrapped an Obama-era rule that required businesses with more than 100 employees to report salary data by race, gender and occupation.

“Blocking this rule is a big step backward in effectively addressing the wage gap,” she said.

“Having companies report that data provides them real incentive to look at their own pay scales and, if there are discrepancies between how they pay men and women, to look at ways to fix it if there isn’t a good reason – experience, performance, et cetera – for those men to make more.”

Progress that has been made came slowly.

In 1976, Heidi Hartmann, a programer with a PhD in economics, was working as a researcher for the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, an agency created in part to address hiring and wage discrimination, when she made an unpleasant discovery. A male colleague doing the same job earned $4,000 a year more.

But when she brought this up to her supervisor, he demoted her.

“They literally told me to do less at work,” recalled Hartmann, who is now 71. She quit, and was quickly hired in the private sector, leaving behind an agency that had failed its mission when dealing with one of its own.

Since around the time Obama took office, public discourse about women in leadership has changed significantly, according to Lyles. “There’s a dramatic increase in how people talk about the issue of pay in the last eight or nine years, but unfortunately there’s a lot that’s still the same.”

Evidence of this status quo isn’t hard to find.

In August, Google came under fire after a memo written by then-employee James Damore went viral. “We need to stop assuming that gender gaps imply sexism,” Damore wrote in his 10-page memo, which was released in the midst of a wage discrimination investigation of Google by the Department of Labor. The agency had found that Google routinely paid women less than men in comparable roles.

This type of stance persists, despite evidence that giving women top jobs may benefit everyone.

“Studies of female leadership have found that having a woman leader creates workplace cultures that are better for women at every level,” said Jessica Bennett, author of Feminist Fight Club: An Office Survival Manual for a Sexist Workplace. But, she said, “It’s not just good for women; it’s good for men, too.”

Bennett noted that research released last year by McKinsey found that gender-balanced leadership leads to higher workplace satisfaction and employee output regardless of the type of organization.

The state has been encouraging more women to apply for jobs, marketing itself as an attractive employer, and to think about moving up the ladder as their careers progress, according to a report it did last year on its gender gap.

“Because most people make career decisions based on who they see working in an occupation and what they know about careers, providing images and quotes by women is critical to successful recruitment efforts,” the report says.

“When an agency is actively recruiting women it is important to be aware of all benefits that may be appealing to women.”

But DeAnda, the ex-state spokesman, conceded that, “I don’t think anything is going to have that big of a difference overnight, from one year to the next. It’s going to take time to turn that tide.”

Though there remains an overall stagnation on this issue, some agencies reported successes. The nearly equal gender pay in Hawaii, for example, is a product of the state having embraced fair compensation for its women for many years, according to one official.

“They have always represented an active and substantial part of the workforce from the early migrants of the late 1800s, working side-by-side with their male counterparts in the sugar and pineapple plantations,” said Linda Chu Takayama, director of the state’s Department of Labor and Industrial Relations. She noted that the cabinet of Hawaii governor David Ige is 50 percent female.

“The nature of the public sector is about collaboration and partnership and figuring out how to make things work between government agencies,” said Vicki Varela, the managing director of Utah’s Office of Tourism and one of the state’s highest paid women employees. “This is work that women are really good at.”

View our searchable database with all pay data here.

A shorter version of this article appeared in the Guardian.